Incontinence Associated Dermatitis

Medline has collaborated with authors Karen Ousey and Louise O’Connor to address this challenging topic. Karen Ousey is Professor and Director for the Institute of Skin Integrity and Infection Prevention at the University of Huddersfield. Louise O’Connor is an Advanced Nurse Practitioner Tissue Viability at Central Manchester Hospital Trust.

They are both experts in the field of Moisture Associated Skin Damage and face this issue on a daily basis as healthcare professionals.

Definition of IAD

Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) describes skin damage associated with exposure to urine or faeces. It causes patients significant discomfort and can be difficult and time-consuming to treat1. It is a significant health challenge and a well documented risk factor for pressure ulcer development2.

The exact size of the challenge for HCPs and patients is hard to define. This is due partly to inconsistencies in terminology, and difficulties in recognising the condition and distinguishing it from Category I/II pressure ulcers in diagnosis: all of which have subsequently resulted in less than robust data collection. This is compounded by the lack of a nationally recognised, validated and accepted method for IAD data collection, which adds to the wide variation in prevalence and incidence figures.

Studies have estimated prevalence of IAD at 5.6% to 50%3-7 while reported incidence varies from 3.4% to 25%8-10.

Patients with IAD may experience discomfort, pain, burning, itching and tingling in affected areas, even when the dermis is intact. In addition to physical symptoms, patients may feel loss of independence, disruption to activities and/or sleep and reduced quality of life that becomes worse as the frequency and quantity of soiling increases. They may also feel/believe they are a burden on family and friends.

References

1Doughty D, Junkin J, Kurz P et al. Incontinence-associated dermatitis. Consensus statements, evidence-based guidelines for prevention and treatment, current challenges J WOCN 2012; 39(3):303-15

2Beeckman D, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. A systematic review and meta analysis of incontinence associated dermatitis, incontinence, and moisture as risk factors for pressure ulcer development. Res Nurs Health 2014; 37:204–18

3Bliss DZ, Savik K, Harms S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of perineal dermatitis in nursing Home residents. Nurs Res 2006; 55(4):243-51

4Peterson KJ, Bliss DZ, Nelson C, Savik K. Practices of nurses and nursing assistants in preventing incontinence associated dermatitis in acutely/critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care 2006; 15(3):325

5Junkin J, Selekof JL. Prevalence of incontinence and associated skin injury in the acute care inpatient. J WOCN 2007; 34(30): 260–9

6Gray M, Beeckman D, Bliss DZ, et al. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: a comprehensive review and update. J WOCN 2012; 39(1): 61–74

7Campbell JL, Coyer FM, Osborne SR. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: a cross-sectional prevalence study in the Australian acute care hospital setting. Int Wound J 2014 doi:10.1111/iwj.12322

8Bliss DZ, Zehrer C, Savik K, et al. An economic evaluation of four skin damage prevention regimens in nursing home residents with incontinence. J WOCN 2007; 34(2): 143-52

9Long M, Reed L, Dunning K, Ying J. Incontinence-associated dermatitis in a long-term acute care facility. J WOCN 2012 39(3): 318-27

10Borchert K, Bliss DZ, Savik K, et al. The incontinence-associated dermatitis and its severity instrument: development and validation. J WOCN 2010; 37(5): 527–35

Costs and Constraints of IAD

Accurate costs related to IAD are difficult to present, as there is little data that distinguishes these from pressure ulcer costs. However, Bale et al1 have explored costs in terms of nursing time and consumables in relation to managing and treating IAD. Following the introduction of structured skin care regimens, over a three months period, in two nursing homes the presence of IAD and Category I pressure damage was reduced with a reduction in time taken to deliver skin care, saving just over 34 minutes of staff time per patient per day.

The average saving per day per patient in staff costs was £8.83 (US $13.75) for qualified staff and £3.43 (US $5.33) for unqualified staff (based on 2004 costs). Guest et al2 evaluated the economics of four different skin care regimens in over 900 nursing home residents, it showed no significant difference in IAD rates between the four regimens, however the total cost (including product, labour and other supplies) per incontinence episode was significantly lower when a barrier film was used.

Psychosocial, Wider Healthcare Organisation Costs

Clinicians are aware that IAD causes pain and discomfort to patients, a stance supported by research from Fader et al3. This highlights that both urinary and faecal incontinence have a profound and devastating effect on a person’s social, physical, financial and psychological wellbeing. Yet patients still experience pain, discomfort and effects on their dignity because of the poor management of IAD.

Dorman et al4 reported that faecal incontinence in hospital patients is often over looked with management of the problem being given low priority. At a time when the health service needs to be aware of expenditure, it is difficult to assess the expense of barrier products and continence aids.

Within the NHS, cost of products is often calculated by reviewing price per unit and amount of products purchased. However, these costs can be unreliable due to insufficient monitoring of incidence and prevalence of IAD making it difficult to fully understand the financial costs associated with this issue. Regular audit of practice, appropriate use of products and their effectiveness would allow for estimates of the true cost of managing IAD and the impact on the NHS.

Impacts on Outcomes and Human Cost of Not Managing IAD Effectively

IAD can be undignified and painful for individuals. A number of patients who suffer from IAD are often reliant on others to help manage their continence issues; unfortunately there is limited empirical evidence to support this.

However anecdotal evidence from those caring for these patients suggest that IAD has a negative impact on patients’ quality of life. This is usually demonstrated by the pain and discomfort they express when suffering with IAD and undergoing treatment.

References

1 Bale S, Tebble N, Jones V, Price P. The benefits of implementing a new skin care protocol in nursing homes. J Tissue Viability 2004; 14(2): 44-50

2Guest JF, Greener MJ, Vowden K, Vowden P.Clinical and economic evidence supporting a transparent barrier film dressing in incontinence-associated dermatitis and peri-wound skin protection. J Wound Care 2011 20(2): 76, 78-84

3 Fader M, Cottenden AM, Getliffe K. Absorbent products for moderate to heavy urinary and /or faecal incontinence in women and men (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 8 (4): CD007408

4 Dorman BP, Hill C, McGrath M, Mansour A, Dobson D, Pearse T, et al. Bowel management in the intensive care unit. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 2004; 20(6):320-9

Differentiate IAD from Pressure Ulcers

IAD and pressure ulcers have a number of risk factors in common with both likely to occur in patients with underlying poor health and restricted mobility1-2. However, there are distinct differences. It is important that clinicians are aware of and recognise the differences that exist between IAD and pressure ulcers.3 If the patient is not incontinent it is not IAD.

Differentiation Between IAD and a Pressure Ulcer*

Parameter

IAD

Pressure Ulcer

History

Urinary and/or faecal incontinence

Exposure to pressure/shear

Symptoms

Pain, burning, itching, tingling

Pain

Location

Affects:

- perineum, perigenital, peristomal area;

- buttocksgluteal fold;

- medial and posterior aspects of upper thighs;

- lower back;

- may extend over bony prominence.

Usually over bony prominence or associated with location of medical device

Shape/edges

Affected area is diffuse with poorly-defined edges/may be blotchy

Distinct edges or margins

Presentation/depth

Intact skin with erythema (blanchable/non-blanchable), with/without superficial/partial-thickness skin loss

- Presentation varies from intact skin with non-blanchable erythema to full-thickness skin loss

- Base of wound may contain non-viable tissue

Other

Secondary superficial skin infection (e.g. candidiasis) may be present

Secondary soft tissue infection may be present

*adapted from Back et al, 2011 and Beeckman et al, 2011; published by Wounds International 2015

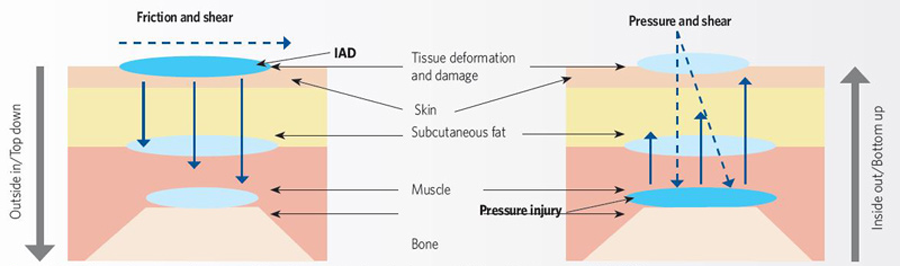

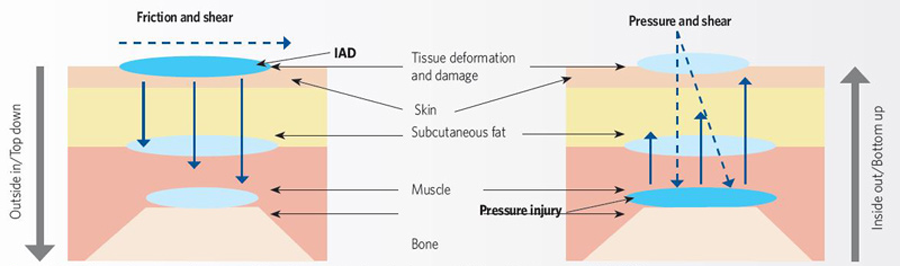

Possible mechanisms of action in IAD and pressure ulcer development

IAD has different aetiologies from pressure ulcer but the two can co-exist. IAD is a ‘top down’ injury where damage is initiated on the surface of the skin; conversely pressure ulcer develops when damage is initiated by changes in the soft tissue below and within the skin and it is, therefore, coined a ‘bottom up’ injury4.

Grading of IAD

In 2011, Bianchi and Johnstone5 found that there was no consistency in the language clinicians use to describe the degree of IAD. To minimise inconsistency in accurately grading the degree of skin damage and to aid development of management strategies, the National Association of Tissue Viability Nurses Scotland (NATVNS) established an excoriation grading tool. It comprises clinical images, grades the level of excoriation and offers management solutions. The tool is also designed to encourage a consistent approach to IAD care6.

Severity of IAD

Signs**

No redness and skin intact (at risk)

Skin is normal as compared to rest of body (no signs of IAD)

Category 1 - Red* but skin intact (mild)

Erythema +/- oedema

Category 2 - Red* with skin breakdown (moderate - severe)

As above for Category 1

- +/- vesicles/bullae/skin erosion

- +/- denudation of skin

- +/- skin infection

References

1 Langemo D, Hanson D, Hunter S et al. Incontinence and incontinence-associated dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care 2001; 24(3): 126-40

2 Demarre L, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, et al. Factors predicting the development of pressure ulcers in an at-risk population who receive standardized preventive care: secondary analyses of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2014; Aug 19. doi: 10.1111/jan.12497

3 Beeckman D et al. Proceedings of the Global IAD Expert Panel. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: moving prevention forward. Wounds International 2015. Available to download from www.woundsinternational.com

4 World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) Consensus Document. Role of dressings in pressure ulcer prevention. Wounds International 2016

5 Bianchi J, Johnstone A. Moisture-related skin excoriation: a retrospective review of assessment and management across five Glasgow Hospitals. Oral presentation 14th Annual European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel meeting. Oporto, Portugal, 2011

6 Bianchi. Top tips for identifying a moisture lesion. Wounds UK 2012; Vol 2: 23–6

Prevent Skin Damage from Moisture

What assessment tools are available currently?

- IAD Assessment Intervention Tool (IADIT)1

- Incontinence-associated dermatitis and its severity (IADS)2

- Skin Assessment Tool3-4

- IAD Severity Classification Tool (currently being validated)5

- Perineal Assessment Tool6

- Perirectal Skin Assessment Tool7-8

Are there any other assessment tools available?

The All Wales Tissue Viability Nurse Forum and All Wales Continence Forum recommends using the All Wales Continence Bundle and the All Wales Bladder and Bowel Pathway9. It suggests the initial patient assessment should include a complete clinical history, physical examination including visual examination of perineal areas to exclude other pathologies (such as allergies or atrophic vaginitis), an assessment of mobility, dexterity and cognitive function, urinalysis, a frequency volume chart and a bowel diary, a post-void residual urine test and a review of the patient’s medication.

It is essential that clinicians accurately assess the cause of skin damage allowing for correct diagnosis of IAD or pressure ulcers. All patients with urinary and/or faecal incontinence should be assessed regularly to check, monitor and document signs of IAD. Clinicians should check for signs at least once daily, increasing regularity of checks based on the number of incontinence episodes. During checks, special attention should be given to skin folds or areas where soilage or moisture may be trapped. Regular assessment results in timely and appropriate skin cleansing and protection, which can prevent and manage IAD.

Skin assessment for incontinence patient at risk of IAD

Areas of skin that may be affected include:

- Perinium

- Perigenital areas

- Buttocks

- Gluteal fold

- Thighs

- Lower back

- Lower abdomen and skin folds (groin, under large abdominal pannus etc…)

These areas should be checked for:

- Maceration

- Erythema

- Presence of lesions (vesicles, papules, pustules etc…)

- Erosion or denudation

- Signs of fungal or bacterial skin infection

References

1 Junkin J. An incontinence assessment and intervention bedside tool (IadIt) assists in standardising the identification and management of incontinence associated dermatitis. Poster presented Wounds UK, Harrogate 2014

2 Borchert K, Bliss DZ, Savik K, et al. The incontinence-associated dermatitis and its severity instrument: development and validation. J WOCN 2010; 37(5): 527–35

3 Beeckman D, Woodward S, Gray M. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: step-by-step prevention and treatment. Br J Community Nurs 2011 16(8):382–9

4 Kennedy KL, Lutz L. Comparison of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of three skin protectants in the management of incontinent dermatitis. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Advances in Wound Management 1996

5 Beeckman D et al. Proceedings of the Global IAD Expert Panel. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: moving prevention forward. Wounds International 2015. Available to download from www.woundsinternational.com

6 Nix DH. Validity and reliability of the Perineal Assessment Tool. Ostomy/Wound Management 2002; 48(2):43-46, 48–49, 51

7 Brown DS. Perineal dermatitis: can we measure it? Ostomy/Wound Management 1993; 39(7): 28–30

8 Brown DS, Sears M. Perineal dermatitis: a conceptual framework. Ostomy/Wound Management 1993; 39(7): 20-22, 24–5

9 All Wales Tissue Viability Nurse Forum and All Wales Continence Forum. Best Practice Statement on the Prevention and Management of Moisture Lesions 2014. Available from: http://www.welshwoundnetwork.org/files/5514/0326/4395/All_Wales-Moisture_Lesions_final_final.pdf

Prevention and Treatment of IAD

Ultimately the goal of a clinician treating a patient with IAD is to manage incontinence1. In order to achieve manage a patients skin effectively a structured cleansing and protection routine should be implemented and evaluated.

Managing incontinence

To assist clinicians in managing incontinence the cause needs to be identified and a plan of care implemented. The European Association of Urology (EAU) Working Panel on Urinary Incontinence (UI)2 agrees that a clear patient history should be taken when assessing a patient with incontinence.

This assessment should include details of type, timing and severity of UI that will allow for a diagnosis of stress, urgency or mixed urinary incontinence. For the older person the EAU advises that physiological changes with ageing lead to UI becoming more common and co-existent with comorbid conditions, reduced mobility and impaired cognition.

For reversible causes Gray3 suggests non-invasive interventions including toileting techniques or nutritional and fluid management with Palese, Carniel4 recommending incontinence management products that can manage fluids. Morris5 identifies invasive interventions as including indwelling catheters, faecal management systems and faecal pouches3. A structured skin care protocol should be implemented for every patient.

A structured skin care regimen

Skin cleansing

As part of the prevention and management of IAD it is important that skin cleansing takes place.

Cleansing of the skin should occur following every episode of incontinence to ensure that the natural function of the skin is maintained. This is supported by a Wounds UK 2012 Best Practice Statement6 which states that when the skin is exposed to urine and faeces the pH around the perinatal changes, increasing lipase and protease activity, causing an increase in skin permeability and reducing the skins natural barrier function.

The use of soaps to cleanse the skin should be avoided as these can dehydrate the skin and cause irritation7. The use of cleansing/moisturising products is preferable.

Products may include foam cleansers, wipes or emollients that cleanse the skin and moisturise at the same time thus reducing skin irritation and dehydration. Manufacturers instructions should be followed at all times when using products to ensure effective and safe use.

Following cleansing of the skin to avoid further irritation and skin damage caused by excessive moisture, it is advisable to pat the skin dry rather than rub the skin which can cause breakdown, pain and discomfort.

Skin protection

The principle of applying skin barrier products is to avoid tissue breakdown.

There are a number of products available that may help to maintain the natural barrier function of the skin. Remember each product should be applied as per manufactures instructions.

Products are available as creams, wipes, sprays and foam films. Cream products often require applying following each incontinence episode, although some preparations claim 72 hours protection time. Skin should be assessed individually with clinical judgement used to decide appropriate reapplication times. Creams should be applied thinly to ensure they are absorbed into the skin providing effective protection and preventing continence aids, such as pads, from losing their absorbency.

When considering an appropriate barrier product, clinicians need to be aware of functions of the product. Products tend to form either protective or moisturising barriers: protective barriers with silicone polymers contain dimethicone, which creates a dry water-repellent barrier protecting against excess moisture; moisture barrier products lock in moisture to hydrate and protect the skin8.

IAD Treatment pathway algorithm

References

1 Cooper P. Skin care: managing the skin of incontinent patients. Wound Essentials 2011; 6: 69–74

2 Lucas M G, Bedretdinova D, Berghmans LC et al. Guidelines on Urinary Incontinence. European Association of Urology 2016. Available from: www.uroweb.org

3 Gray M. Incontinence associated dermatitis in the elderly patient: Assessment, prevention and management. J Geriatric Care Med 2014. Available from: http://bit.ly/1HBbjS6

4 Palese A, Carniel G. The effects of a multi-intervention incontinence care program on clinical, economic, and environmental outcomes. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011; 38(2): 177-183

5 Morris L. Flexi-Seal faecal management system for preventing and managing moisture lesions. Wounds UK 2011; 7(2): 88-93

6 Best practice statement: Care of the older person’s skin. Wounds UK, London Wounds UK. 2012.

7 Bale S, Tebble N, Jones V, Price P. The benefits of implementing a new skin care protocol in nursing homes. J Tissue Viability 2004; 14(2): 44-50

8 All Wales Tissue Viability Nurse Forum and All Wales Continence Forum. Best Practice Statement on the Prevention and Management of Moisture Lesions 2014. Available from: www.welshwoundnetwork.org

Moving Forward with IAD

Reducing knowledge gaps

There has been a range of campaigns to raises awareness of pressure ulcer prevention over the past decade, including campaigns and the introduction of a range of care bundles including, SSKIN.

These have resulted in a heightened awareness and understanding of prevention, management and treatment of pressure damage that has successfully reduced incidence. There now needs to be similar campaigns to raise awareness and understanding of IAD in healthcare with updates for pressure ulcer prevention including IAD.

Product selection remains a challenge for clinicians when preventing and managing IAD due to a lack of knowledge and clinical evidence1.

There is a need for a randomised controlled clinical trials to test the efficacy and effectiveness of skincare products that will assist in standardising outcome definition and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Production of standard statements to promote best practice and agreed terminology for skin damage caused by excessive moisture would also allow for practice to be measured and improved against national guidance.

The need for standardisation of terminology, diagnosis and care

How could this be achieved and what improvement would it bring to patients, clinicians and payers?

Beeckman et al1 highlighted the importance of agreeing and recognising consistent terminology for IAD arguing that the World Health Organization’s International Classification of diseases does not contain separate coding for IAD. Currently only diaper dermatitis is recognised.

Beeckham et al2 suggest that IAD should be clearly differentiated, defined and included in the International Classification of Diseases, which would facilitate research and improve education of healthcare providers. Consistent terminology relating to pressure ulcers has allowed organisations to benchmark internally, locally and nationally.

It is essential that healthcare organisations work together to provide clear assessment, treatment and evaluation strategies to recognise and manage IAD. This will allow for continuity of care by healthcare providers, education for clinicians and patients.

References

1 Beeckman D, Van Damme N, Van den Bussche K, De Meyer D. Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD): an update. Dermatological Nursing 2015; 14(4): 32–6

2 Beeckman D, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. A systematic review and meta analysis of incontinence associated dermatitis, incontinence, and moisture as risk factors for pressure ulcer development. Res Nurs Health 2014; 37:204–18

Related Products